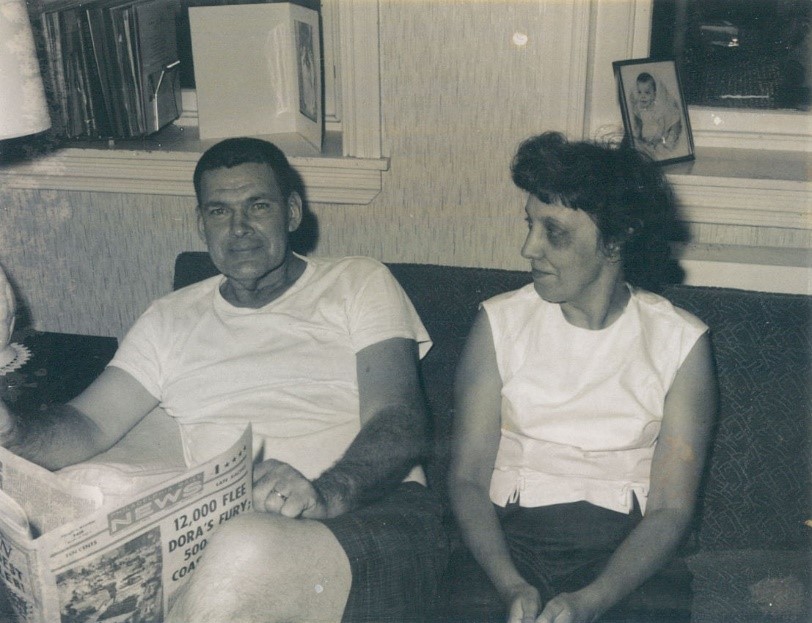

We were sitting in the family room in their little cape cod in Elverson PA, watching Lawrence Welk. I knew it would probably be the last time I saw Pop-pop this side of heaven. I was leaving for a semester abroad during the fall of my junior year of college, and he was dying. A guest on the show sang the beloved hymn, “How Great Thou Art,” and Pop-pop and Grandmom sang along, tears streaming down their faces.

Lawrence Welk was a show I only ever watched with my grandparents. They loved it, and they loved me. Many weekends during my growing-up years, I escaped the rough and tumble household of my four brothers and stayed overnight with them. They let me stay up late and sleep in, and I befriended their neighbors. One neighbor gave me riding lessons and the other gave me flute lessons. I loved the individual attention I got at Grandmom and Pop-pop’s house. Even when the whole family gathered, I always claimed my spot next to him. His nick-name for me was Blondie, and when we said good-bye, he always said, “Stay as sweet as you are.” It seemed like he was the only one, including me, who believed I was sweet.

Lawrence Welk was a show I only ever watched with my grandparents. They loved it, and they loved me. Many weekends during my growing-up years, I escaped the rough and tumble household of my four brothers and stayed overnight with them. They let me stay up late and sleep in, and I befriended their neighbors. One neighbor gave me riding lessons and the other gave me flute lessons. I loved the individual attention I got at Grandmom and Pop-pop’s house. Even when the whole family gathered, I always claimed my spot next to him. His nick-name for me was Blondie, and when we said good-bye, he always said, “Stay as sweet as you are.” It seemed like he was the only one, including me, who believed I was sweet.

I’m not sure if he was your typical grandfather if there even is such a thing. During those aforementioned dinners, he’d stick his false teeth out at us, tell colorful stories about his truck-driving days, and use words we were later told we should not repeat. He was stubborn, and one time, after discovering he was wrong about the location of a certain town, he insisted that they moved it. He was a trustee in the little country church down the road, and he rarely missed a Sunday as far as I know. He was full of contradictions, but we kids all adored him.

We knew he was a veteran because I remember my grandmother hooking a large rug depicting emblem of his unit. Maybe I wasn’t listening when he told stories about the war, or maybe he never did. I do, however, remember vividly what he told me that last night I spent with him before I left for my semester in Germany.

“Don’t you tell them over there that you know me,” he said. His light blue eyes were cloudy with age and a little watery.

Like many of the volunteer crew for The Girl Who Wore Freedom, I first heard about the project on the Holy Post podcast. As part of the transcription team, I worked on correcting the transcriptions of the video interviews Christian had collected on her many visits to Normandy. The stories of the veterans captured me, and I thought about my grandfather.

We had been saving for a trip out west, but when Christian emailed about the Normandy focus group events, we decided to change our plans and travel to France for the 75th anniversary of D-day. That was the first time I researched my grandfather’s years of service. Before then, I was never that interested, mostly because to me, Pop-pop and Grandmom’s house was my place of refuge. I confess I was the center of my universe, and in my self-centered immature thinking, they existed to make me feel special and loved. I never gave a thought to their lives before mine.

We had been saving for a trip out west, but when Christian emailed about the Normandy focus group events, we decided to change our plans and travel to France for the 75th anniversary of D-day. That was the first time I researched my grandfather’s years of service. Before then, I was never that interested, mostly because to me, Pop-pop and Grandmom’s house was my place of refuge. I confess I was the center of my universe, and in my self-centered immature thinking, they existed to make me feel special and loved. I never gave a thought to their lives before mine.

A quick online search revealed the following — My Pop-pop, Charles H. Evans, was in the 807th Tank Destroyer Battalion. They arrived at Utah Beach on September 18, 1944, and fought in their way through Germany throughout that winter. They reached the vicinity of Salzburg, Austria in May 1945. As I read the short paragraph, I vaguely remembered him mentioning Rhine River bridges they defended. I saw on-line a photo of his unit, one which I remembered seeing among his belongings.

For reasons that don’t seem to make sense now, I was unprepared for the rush of emotions that would well up in me when we visited Normandy. After all, he didn’t actually participate in the D-day landings, and he wasn’t involved in any of the huge historic battles that were memorialized in the museums.

We entered Sainte Marie du Mont on the 7th day of our visit, and I was still searching for a sweatshirt or t-shirt commemorating our visit. We were in the line of cars entering the little town when I saw a sign for Army memorabilia. I hopped out, promising to catch up to the rest of our family when they found a place to park. When I walked in, I realized this was a different type of store. Instead of seeing souvenirs aimed at modern tourists, I saw vintage army jackets, boots, shoes, and hats. I poked around, curious. In a display case at the counter, I looked down, and there was the patch with the emblem of the 807th, the one I remembered from Grandmom’s rug, the tiger crushing a tank in his jaws.

The store clerk saw my face. “Mon Grandpere” I managed to say. “Grandfather,” she said. She took the patch out of the case, and I held it in my hand. It was no reproduction; it was worn and soft. Thirty Euros. I bought it.

The store clerk saw my face. “Mon Grandpere” I managed to say. “Grandfather,” she said. She took the patch out of the case, and I held it in my hand. It was no reproduction; it was worn and soft. Thirty Euros. I bought it.

That afternoon, as we walked the streets of Ste. Marie du Mont, the realization hit me full force. My grandfather had been there. He walked those very streets. He was 32 years old. Perhaps he had been one of the soldiers who interacted with the French children at the camp in the church square before heading inland, pushing forward for freedom.

He came home, met and married my grandmother, drove a truck, kept his secrets, and loved his grandchildren and his Lord. Did I ever thank him for his service? Would saying thank you be enough? He gave those years of his life and bore the emotional scars of war. He didn’t sacrifice his life, but I wonder if he sacrificed his sense of well-being. Like many veterans, he buried the painful memories of combat, and that pain inevitably poisoned the soil in some of the most damaging ways.

Later on that day, I flew a flag on Utah Beach to honor his memory and his service. As I write this now, I know that that act does not erase the pain of war. It does not erase the damage his buried pain caused in his most important relationships. It does not change the fact even when he was dying, he was troubled by the things he had seen and done as a soldier. However, flying that flag on that day and wearing his patch on my jacket is a way for me to finally acknowledge his life as more than just my Pop-pop. He was a man did what he thought was right, and whose life was marked by that experience.

Later on that day, I flew a flag on Utah Beach to honor his memory and his service. As I write this now, I know that that act does not erase the pain of war. It does not erase the damage his buried pain caused in his most important relationships. It does not change the fact even when he was dying, he was troubled by the things he had seen and done as a soldier. However, flying that flag on that day and wearing his patch on my jacket is a way for me to finally acknowledge his life as more than just my Pop-pop. He was a man did what he thought was right, and whose life was marked by that experience.

As I reflect on that time in Normandy, I remember also that day in their family room, with Lawrence Welk on the TV. After walking where he walked and imagining him there, I am filled with gratitude. I’ve always been grateful for the memories of his teasing and his rough hands tickling my ear, his unconditional love and favor. I’ve always been grateful to have him as my Pop-pop. Now, however, I’m grateful for more than just that – I’m grateful for the way that love overcame the pain. I’m grateful for his sacrifice, and for the promised healing of heaven. I’m not sure what I did that day as Grandmom and Pop-pop sang and wept. I was unused to seeing such displays of emotion, but I know that my heart wanted to join in their embrace and declare the greatness of a God that welcomes weary soldiers home.

This post was authored by:

Thank you for sharing

Thanks for reading and commenting, Sandy. Sharing this experience helped me process both grief and gratitude.

Laura, this is beautifully written. I can feel the love you still have for your Pop-pop. You honor him and all soldiers who hold their personal stories of battle close to their hearts.

Thanks, Donna! The trauma that soldiers endure has ripple effects, but thank God there is healing!

Beautifully written Laura, this was very moving. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks, for reading and commenting, Beth!

Hi Laura,

What a tender story, partially lived with your grandparents…their gift of grace and acceptance and the mostly untold story of your Pop Pop’s experience of the war and the pain that was hidden and unhidden.

MAy those who have served find a gracious space to share what would be important and may the work related to trauma of war violence and other forms as well be available for those who need it. Thank you, Sibyl

Your comment means so much, Sibyl, and I join you in that prayer for all who’ve experienced trauma of any kind.

What a touching remembrance and act of love to hold your grandparent’s stories as a precious part of your own. It is an act of love to remember. Thanks for your story, Laura.

Oh, Sharon, that’s so true about remembering! It is an act of love, and a labor to allow ourselves to remember in the light of where we have come ourselves….thanks so much for reading & commenting.

Beautiful memories Laura!

Thanks, Rick! I know you could share some as well!

Beautiful remembrance, Laura. Loved your blog and was so moved by the tribute to your grandfather when first posted but even more so now after our time together in Ohio. Thank you for sharing your journey with your grandparents.